Buenos Aires, Argentina – After a marathon 12-hour session, Argentina’s lower house of Congress narrowly approved a controversial labor reform bill, in what is shaping up to be a significant victory for President Javier Milei.

The vote came in the early hours of Friday after a national strike in protest of the bill caused widespread factory and business shutdowns.

Recommended stories

list of 3 itemsend of list

“We took another step on the road to making Argentina great again,” Gabriel Bornoroni, a lawmaker in Milei’s party, La Libertad Avanza, wrote online after the vote.

The Bill issues new rules to govern relations between workers and employers. It is expected to become law before the end of the month, after the Senate reviewed amendments to the version it first passed last week.

Members of La Libertad Avanza say the legislation will modernize the labor market by making it easier for companies to hire and fire workers, including through restrictions on austerity payments and collective bargaining.

It also allows employers to extend the workday from 8 to 12 hours, creates a “time bank” to replace paid overtime and reduces the amount of uninterrupted vacation a worker can take, among other provisions.

Supporters argue The changes are essential to boost productivity, attract foreign investment and limit labor lawsuits.

They also praised provisions that offer new tax incentives for hiring and pathways to legally register Argentina’s large population of informal workers.

“We have labor modernization. Javier Milei gives answers to the millions of Argentines currently in the informal economy,” Bornoroni posted on social media after the vote.

Since the bill was first drafted, business leaders have been divided over its potential effectiveness.

Some have warned that its provisions, including those affecting collective bargaining and contract stability, could create feelings of insecurity among employees.

Others questioned how much it would increase hiring. Ricardo Diab, president of the Argentine confederation of medium-sized enterprises (CAME), said in an interview with Cadena 3 that a law alone is not enough to create jobs.

“To hire (people), I have to have a need, and to have a need, there has to be production and consumption,” he said.

Meanwhile, opposition politicians and trade unionists argue that the law will strip workers of their basic rights.

“Workers were already under pressure, and this just delivers another heavy blow, leaving them with very little room to negotiate anything,” Roxana Monzon, a national deputy for the opposition party Union por la Patria, told Al Jazeera.

“This means job insecurity for workers, and it will affect the most vulnerable even more.”

She pointed to the “time bank” as an example of the bill’s problematic proposals.

Instead of mandating paid overtime, the legislation would allow employers to compensate workers with time off later, subject to company approval.

That system, Monzon explained, is ripe for exploitation, as some workers rely on overtime to pay the bills.

“For example, the hour bank will particularly affect women, as employers can decide what hours they should work, regardless of other responsibilities they have, such as caring,” Monzon said.

Anxiety among workers

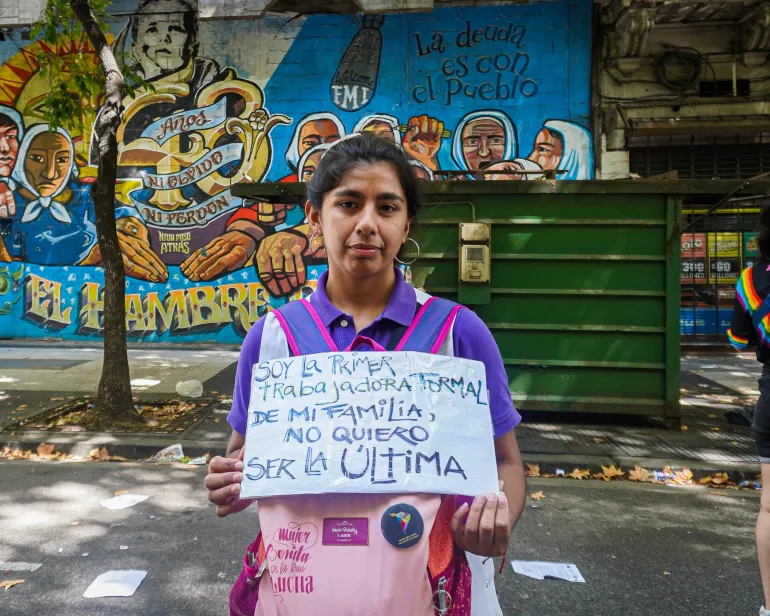

As members of Argentina’s Chamber of Deputies debated the bill on Thursday, thousands of people protested outside Congress in solidarity with a nationwide strike organized by the country’s main unions.

Gabriela Quiroz, a 31-year-old primary school teacher from Villa Soldati, near Buenos Aires, said she was already working two jobs to make ends meet. She described the bill as an “abysmal step backwards”.

“I’m very worried and anxious about what could happen. As a teacher, I do a lot of extra hours, and now they won’t be paid in cash,” Quiroz said. “I barely make it to the end of the month as it is, and there are a lot of people like me.”

She added that lowering overtime pay could have a greater impact on Argentina’s economy, with consumers spending less.

“When people don’t have money, everyone is affected,” she said. “If I don’t have money to spend, I don’t shop in my local stores, so they start to struggle. It’s a vicious cycle.”

Quiroz was one of the thousands of people who made their way to Congress, undaunted by the heat and the lack of public transportation, one of the services disrupted by the strike.

The general strike also left airports empty as hundreds of flights were cancelled. Factories and banks also closed for the day, and hospitals provided only emergency services.

As protests in Buenos Aires came to an end that evening, security forces used water cannons, tear gas and rubber bullets against the protesters, a violent response that became increasingly common.

Thousands of businesses closed

The labor market has become a central concern in Argentina amid a deep economic recession. The bill tries to address the issue from several angles.

Think tanks such as the Argentina Institute for Fiscal Analysis have reported that companies face high costs of hiring new workers, and as many as 40 percent of Argentina’s workers work in the informal sector, without job protection.

The bill offers incentives to address these issues. But analysts say what is needed is a broader look at the country’s economy.

While economic activity has generally increased in Argentina, that growth has been uneven. While sectors such as banking and agriculture have improved, manufacturing and trade have experienced sharp declines in recent years.

More than 20,000 businesses with registered employees closed between November 2023 and September 2025, at a rate of about 30 per day, according to the Center for Political Economy in Argentina (CEPA), a think tank.

During the same period, CEPA added, approximately 280,000 workers lost their jobs.

Stagnant wages have also struggled to keep up with price increases for basic products and services like food.

“While we’re in Congress, we’re debating the cost of employing people, in many homes, families are debating whether their children can continue to go to school or get any jobs to help pay for rent and food. Everything breaks at the weakest link,” Monzon said.

Significant victory

In political terms, analysts meanwhile say the bill represents a show of strength from Milei and his party.

Milei, who was in Washington, DC on Thursday, celebrated the bill’s success with a mail on X.

“Historic. Argentina will be great again,” he wrote, putting his spin on a slogan popularized by US President Donald Trump.

Andres Malamud, a senior research fellow at the University of Lisbon’s Institute of Social Sciences, said that for a country like Argentina, with a heavily regulated economy, the labor reform is not the most important bill, but it is the most symbolic.

It deals a blow to the historic power of Argentina’s unions, which have long been associated with Peronism, the political movement that has ruled since 1946, Malamud explained.

Milei, meanwhile, rejected Peronism, and his party won a decisive victory against the leftist Peronist movement in October during Argentina’s mid-term elections.

“If international conditions do not worsen and social patience lasts, Milei will have achieved what no president has achieved since 1983: to rule longer than non-Peronists while reforming more than Peronists,” Malamud said.

Meanwhile, in Buenos Aires, Susana Amatrudo (54), a nurse from Avellaneda, told Al Jazeera she fears the changes will have a ripple effect across society.

“When factories close, and people lose their jobs, it affects everyone. People have less money, and they can buy less. It’s been happening for a while and will only get worse,” Amatrudo said, tears streaming down her eyes as she waved a large Argentine flag in front of Congress.

“I’m fine, but I know a lot of people who aren’t, and that’s why we have to keep fighting.”

![[keyword]](https://learnxyz.in/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/1771654995_Argentinas-Chamber-of-Deputies-adopts-controversial-labor-reform-bill.jpg)

![[keyword]](https://learnxyz.in/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Kit-Harington-gags-with-Sophie-Turner-after-kissing-her-in.png)

![[keyword]](https://learnxyz.in/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Iran-seeks-to-get-off-FATF-blacklist-amid-domestic-political.jpg)